Raj Nair (Chairman – Avalon Consulting), Ayush Patodia (Senior Consultant) & Ganesh Shewatkar (Consultant) shared their opinion with The Financial Express (India) on the reasons behind the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. They also offered their views on the implications of the event for India’s financial institutions and the startup ecosystem.

The fundamental principle in banking business is to have effective risk management. In India, Raghuram Rajan introduced very effective multistage risk management controls, including limits on single company exposure, group exposure, industry exposure, asset / liability matching, stress tests, cross company ever greening of loans, risk-based supervision, and prompt corrective action frameworks. All these measures existed earlier also but only on paper. Rajan enforced them in letter and spirit.

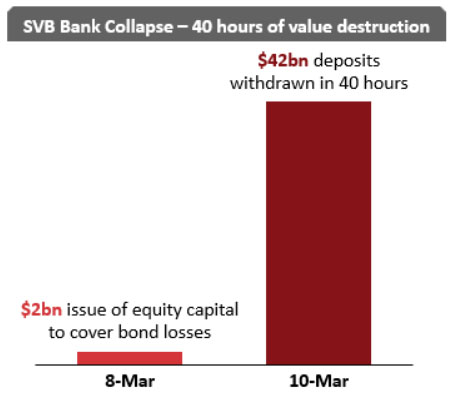

The Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) collapsed because of breaking the industry exposure norms. Almost 100% of SVB’s exposure was to the tech industry, which is highly sensitive to interest rates. When interest rate was near zero for over 10 years, PEs / VCs parked their funds in startups and early stage tech companies as equity. Those companies in turn deposited the cash with SVB and drawing down for monthly expenses depending on their burn rate. But the float of deposits with SVB ballooned to $180 B! SVB in turn bought 2/5 years treasury bonds. When interest rate was raised in stages, bond values started collapsing. Initially it was just paper losses. When SVB’s equity was fully eroded, they announced fresh equity raising for $2.3 B. Existing shares tanked 67% on the same day. All their clients started withdrawing deposits. Paper losses turned into real cash losses and a run on the bank started later in the day.

AFS (Available for Sale) is a typical US accounting trick. Banks in India and in most parts of the world, had either HTM (Hold to Maturity) or MTM (Marked to Market) trading portfolios. But in the USA, you could hold the paper in, not mark it to market, but shift it to either HTM or the trading portfolio when you chose to. US banks generally use this for holding bonds and selling them when yields go down and that helps to juice up profits. When interest rates in USA went up from 0 to 5%, bond yields dropped but SVB could hold their AFS as HTM. So, no losses. But their greed knew no bounds. They did not hedge on interest rates even as they watched interest rates shooting up. This is sinful but it avoided paying interest hedging costs.

In SVBs case, the MTM loss on the HTM portfolio spooked some people, triggering withdrawals and creating a Liquidity crisis. SVB was forced to sell AFS bonds which were HTM, to pay for withdraws. Automatically then, losses got booked on the AFS. But withdrawals shot up due to panic, wiping out the entire capital of the Bank. The basic problem is that the size of their AFS portfolio was allowed to get much larger than it should have, in a prudential set up. Earlier Banks with below $50 billion assets, were not under strict FED scrutiny. But under Trump, lobbying by the big players raised that limit to $250 billion. So SVB happily grew rapidly to $220 billion in assets and stayed $20-30 billion under the radar.

The collapse of SVB has sent shockwaves through the global banking system, with many other banks becoming wary of the contagion effect, although, it is unlikely to have a significant impact on APAC financial institutions. The banking stocks are facing acute selling pressure, which could potentially lead to rupee depreciation and monetary policy by the RBI. The rising interest rates could pose a risk to banks with large holdings of long-term securities. There is a high probability of reduction in capital inflow, which would impact the Indian economy negatively. It has also led to a drop in crude oil prices. The USD rates should remain under pressure till some concrete road map is announced by the government of USA.

On the other hand, the startup world turned upside down, with VCs turning off the funding tap, while asking startups the hard questions about profits. They would have to move to bigger banks which will be safer but have a higher lending cost. Additional services which SVB offered like bridge financing to VC-firms, which enabled them to strike deals while awaiting cash from investors, would also take a hit.

In conclusion, the collapse of SVB highlights the risks associated with concentrated deposits, bad risk mitigation, and lax scrutiny. While the failure of SVB may have some negative effects on the Indian startup ecosystem, the broader banking system is expected to remain robust and resilient. Nonetheless, regulators and policymakers must remain vigilant to ensure that the banking system remains well-capitalized and well-regulated, to prevent similar failures from occurring in the future. Furthermore, the Indian startup ecosystem should consider diversifying its funding sources and reducing reliance on a single institution or country. By doing so, the Indian startup ecosystem can ensure that it remains resilient and capable of sustaining growth, even in the face of external shocks.