This succinct piece is on what, why and how of PLI schemes. It also includes some learnings from the previous government’s production linked schemes, and risks worth noting during implementation.

Are PLI schemes the silver bullet for India’s post-pandemic economic growth?

What is a PLI scheme?

PLI stands for Production Linked Incentives. In this scheme, the Government of India (GoI) incentivises companies for incremental sales (over a base year) of products that are manufactured in India. In simple terms, a reward for increased domestic production.

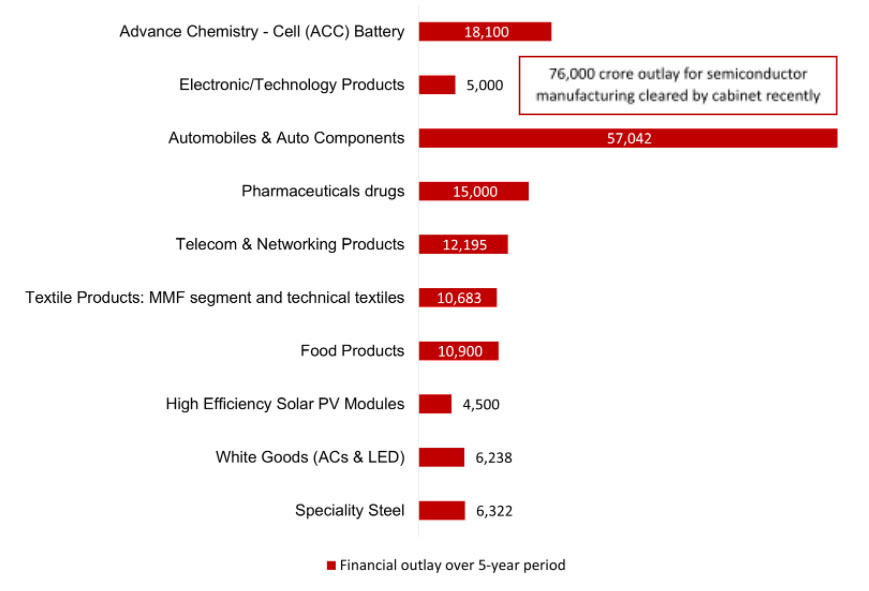

India’s Finance Minister announced an outlay of INR 1.97 Lakh Crores for the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Schemes across 13 key sectors in the Union budget 2021-22. The financial outlay in crores for 10 sectors is shown below.

Why did India choose to start PLI schemes?

The pandemic had severely impacted the Indian economy with GDP contraction of 24.4% YOY in Q1 of FY2021. The other stinging problem was rising unemployment rate that had reached 23% soon after the nationwide lockdown in Apr’20. We know that,

GDP=Consumption+Investment+Government spending+(Exports-Imports)

The focus is on Increasing Exports and Reducing Import bills. This also falls in line with the Make in India initiative which didn’t get the momentum it needed when it was launched. Through PLIs, the government intends to increase exports, reduce imports, create employment opportunities, drive consumption up, and attract more private investments.

The economic survey of 2019-20 also highlighted the necessity for transformation in manufacturing. It advocated the country to be a global hub for assembly operation and value chain manufacturing. To this end, the focus on PLI and encourage MSMEs to play a greater role are the main mantras being followed.

This was also advocated by Professor Arvind Panagariya, saying “India is abundant in labour and assembly of products. It must specialize in these activities across many products.”

Learnings from Phased Manufacturing Programme (PMP) of 2015 – (Electronics Industry)

The PMP was a policy to make India a mobile & component manufacturing hub. The first phase of the program was started in 2015 by making local assembly of mobiles cheaper than imports. This was done by increasing the custom duties on imports of these accessories or components. The policy was later extended to chargers, batteries, and headsets in 2016. The PMP was implemented with an aim to improve value addition in the country.

Official sources claimed that the electronic industry made rapid growth since the past 3-4 years. One of the factors attributed to this growth was the PLI scheme. India’s share in global electronic manufacturing increased to 3.6% in 2019 compared to 1.3% in 2012.

Critics argued that the surge in growth of electronic industry was mainly due to mobile phone production while other areas of electronics witnessed adverse growth. Also, the growth in mobile manufacturing was triggered by Chinese manufacturers who were invited to encourage FDI irrespective of the political face off. The main attraction for the Chinese firms’ investment was demographic advantage of India and rising protectionism through high tariffs.

Another concern of PLI for manufacturers is WTO backlash since the scheme mandates localization in mobile phone and some IT hardware such as laptops, PCs. WTO prohibits discrimination in localization between indigenous and imported products. To this end, some big manufacturers distanced from the scheme, as the WTO backlash cannot be ruled out.

Problem of more imports in India (Electronics industry)

While the production increased from $13.4 billion in 2016-17 to $31.7 billion in 2019-20, the improvement in the local value addition remains a work in progress. Analysis from factory-level production data from Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) shows that in 2017-18, value addition for surveyed firms ranged from 1.6% to 17.4% with most firms being below 10%. For majority of the surveyed firms, more than 85% of inputs were imported. Comparable UN data for India, China Vietnam, Korea, Singapore (2017-19) show that except for India, all counties exported more mobile phone parts than imports indicating presence of facilities that add value to these parts before exporting them. India, on the other hand, imported more than it exported. The new scheme launched in Dec 2021, now extends support up to 50% project cost to set up semiconductor, display fabrication firms. Here’s to hoping the new scheme creates some players from Indian soil with world class scale and technical know-how in the semiconductor industry.

Way forward

Through PLI schemes, the government has taken steps towards increasing domestic production in strategic sectors that can help in India becoming self-reliant and competent manufacturer for the world. But there are risks factors to watch out for during the implementation phase. The PLI already addresses the problem of companies getting the sops for gold plated investments by linking it directly to the output. With increased focus on MSMEs this time, and not just the large cos, which is good, better governance checks and a robust implementation system is to be in place for the sops to reach the right companies. Also, with PLIs, we need to see if value addition in India improves and the goal of reducing imports, increasing exports is realised alongside employment generation. While the direction and foresight of the scheme is promising, we will have to wait and see how it pans out.

Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog owner and do not represent those of people, institution or organizations that the owner may be associated with in professional capacity, unless explicitly stated.

Aravind Subramanian

Aravind is a consulting professional with about 2.5 years of total experience. He has worked on engagements in sales transformation and brand marketing for clients in the Telecom & IT services and Life sciences, respectively. He is an alumnus of SPJIMR Co’21. He is an avid cricketer, loves to travel and explore new places.